In a 1930’s, Cecil Purdy said you could sit down for practice with three chess masters at any time by opening a book of games. In Purdy’s recommended practice method — playing through a master game and guessing the winner’s moves as you go — you’re at the board with three great masters of the past.

The master sitting opposite — the opponent — never says a thing. The master beside you plays with your consultation, but Purdy says he’s very stubborn, and insists on his move. When your guess agrees with the move actually played, excellent! Play the opponent’s move, and guess again.

When your guess doesn’t match, the third master will whisper to you at times: “Ah, we see your point, but our friend here believes in this other move because….” and “Your choice is just as good — maybe better! — as your partner’s choice, but we must go with his.” You retract your move, replace it with the move actually played, make the opponent’s move, guess again.

Do this many, many, many times with a good selection of games. Purdy (and everyone who studies in this fashion) knows it’s discouraging as heck, but with diligence, you’ll guess increasingly longer sequences of moves, while learning to think like a master.

Your consultation partner is the master who won the game you’re playing through, and the master guiding you along is the annotator. I forget which of the Thinkers’ Press collections of Purdy’s articles includes that whimsical metaphor (I might have to open some moving boxes to find my books, but I’ll have to pack them again soon … I think ). I like the metaphorical description better than this drier outline at this site of Purdy sayings, and this distillation in an old newspaper column, because it’s easier to see the value in this form of practice when you think about it like being seated with three masters at once.

I’m an ardent believer in this practice. I’ve played so many games ‘for practice’, read so many books and articles ‘for learning’, but after almost 50 years, I’m sure the only thing that truly helped was guessing moves in two books: Capablanca’s Best Games by Golombek, and Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings by Chernev.

I like the setups that reward you in some fashion. The Solitaire Chess books and articles by Horowitz and Pandolfini put you through this exercise, awarding a score for correct guesses, and a grade at the end. The Guess the Move feature at chessgames.com handles the scoring for you, and its computer grades the quality of your guesses — +3 for a correct guess down to -3 for a serious mistake — then gives you a grade at the end.

For that Guess the Move feature, chessgames dot com is the only subscription-based chess website that deserves my money. You can perform the practice with any digital game by guessing then clicking, but the grades in progress and at the end make it more enjoyable.

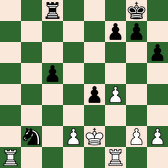

I selected Eisenberg-Capablanca, New York 1909 for guessing a few nights ago. The game has a unique history. Capablanca’s scoresheet was among the items his wife bequeathed to a library, under wraps for so long that the score wasn’t included in the first edition of Caparros’ ‘complete’ anthology of known Capablanca games.

It’s a long game, requiring four practice sessions across three days — I had to sleep three times in the course of playing through it, a luxury Capablanca didn’t have, but in 1909, he was still an energetic college baseball player.

Chessgames dot com tracks the scores of everyone who plays uses their Guess the Move feature, assigning a “par score” from the average. I’m most pleased to say that I wrecked the grade curve: Par was 92, until my 146 raised par to 101.

This is what life with my teacher is like: I crushed the grade curve at chessgames dot com, earning an OUTSTANDING!, but according to my teacher, 45 correct guesses in 56 is worthy of a passing grade, a C.

Source image for thumbnails.