The universe is so weird. Two days ago, a glitch with the web server meant restoring the site from a backup, and having to redo the formatting for three posts.

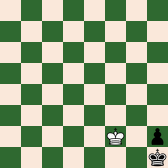

One of those posts was the following about the quirk of king-plus-rook-pawn vs. king endings. Wouldn’t you know it — grandmasters Nakamura and Dominguez played one at the US championship today.

Source image for thumbnails.